Recovering Sanity Session 3: Crowhurst Chapter – Megalomania Is Very Close to Us All

Over the course of the next few months, Windhorse Northampton will be having discussions about Podvoll’s Recovering Sanity which is a principle book towards the Windhorse approach to recovery. The discussion is lectured by staff members and open to the wider Windhorse community. This first post was lectured by Gary Blaser. The following is an edited (for ease of reading) transcript of the lecture.

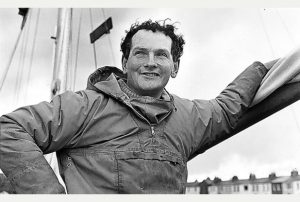

Gary: We’re continuing our passage through the parables, which are found in the first part of the book Recovering Sanity. I’ve been given Donald Crowhurst, who sailed in an around-the-world race in 1969 and disappeared. It’s actually documented that he committed suicide.

What the book says is that we all have the seeds of megalomania and the seeds of our destruction right in that place of ego development—we all have it. I like how Ed Podvoll brings that really close. It’s really easy to look at a sailboat in the middle of the ocean and a guy having dual logbooks and doing all this stuff, and to say, “Wow man, he’s out there.” What Podvoll suggests, and what I’d like us to consider, is that Crowhurst is really, really close to us.

In reading about Crowhurst’s youth and his adventures, we see how he got identified with being brave. I would like you to consider the statement, “I am brave.” There is a way, in terms of healthy ego development, that identifying with being brave is appropriate. For example, when you’re a teenager, you go off and you challenge the hell out of the world. Why not? That’s what you do. That’s a great thing, that’s important, and at the same time, that has in it the seeds of our destruction.

What I appreciate is this iconic predicament that gets set up by the very nature of what Podvoll calls our character, our experiences, or the development of our ego. All these experiences that Crowhurst had, his clashes with the environment, and what we know from Greek tragedy, is that this is a very old story. Podvoll mentions Icarus but just about every Greek tale is about Joe Athenian going along in his life thinking, “I’m all that and a bag of chips! I’m moving along in my life and hey, maybe I know as much as the gods, and maybe I’m going to do this and that.” And then what happens? Bam, he gets beaten down very quickly—so we can see a very archetypical story about ascension and fall. The Greeks portrayed that really well. They knew human psychology very well, and they enacted it in their plays and theology. We can look at Crowhurst as another parable; it’s another look at how we all have the seeds of our own destruction and how we all have that potential to be “crashed down by the gods,” in so many words.

In Latin, the definition of megalomania is “delusions of greatness” and I like the word hubris because that has Greek roots that relate to being an affront to the gods. Hubris is knowing more than the gods in a certain way, so you can see how these themes weave their way into our language. When we think about egomania (or we think about hubris or about ego), we often think about an inflated ego. Crowhurst certainly had an inflated ego. When someone says, “I can do anything. I can overcome any obstacle.” that’s a serious inflation. What I want us to consider, especially for us as human service workers, is that ego really doesn’t care how it’s special. Ego can be special because it is great or the ego can be special because it’s a piece of shit. Ego doesn’t care.

Again, it’s really easy to distance ourselves from Crowhurst and say, “Wow, he was really out there and he was inflated,” but I want to suggest that ego deflation (where I say, “Oh, no I can’t do that,” or “I’m not good enough,”) those sorts of deflated places that we go to, have just as much ego in it as ego-inflation. Both are true and I want to keep holding that because again, I want to keep bringing this home to where we live, and as human service workers, we are absolutely susceptible to both of these energies and forces.

So the seeds of our self-destruction are in our egos. I like how one author describes ego as, “Captain Control,” and its only role is to do whatever it takes to stay safe. In this way, it has its own energy. If we’re not able to separate from it and observe it, it can really take over. I think we’ve all experienced that.

Two Stories Related to Ego

I want to share two stories related to ego. One happened here and one happened a long time ago. There was a time in my life when I was newly sober with all that that takes and feels like. After I got sober, I found I was driving really fast and I loved speeding. I had this belief (and I really believed it) that, “I am protected, man. I am not going to get pulled over. I’ve got magic powers.” I really believed that and I didn’t get pulled over for a year. I didn’t get pulled over for two years, but then in that third year, bam, bam, bam. Within two months I was in driver education thinking, “How did I get here? I was protected.” Fortunately it was driver’s education and not the hospital. That’s how close this is for me. It’s not far away.

Then there was one time here when I was in supervision with Mary, and I had a case that was really challenging. One of the things for me working here is the struggle of trying to will my clients to feel better. I can have this sense that I know what’s good for them, and I can feel really attached to them doing what I think they should be doing. There’s a real easy way to get attached to that perspective. I was lamenting with Mary in supervision one day, saying, “God, he won’t do this and he won’t do that, and he’s blah, blah, blah, and he’s never going to blah, blah, blah” and she looked up and goes, “What if he doesn’t have to change?”

It was like somebody took a hatchet and just went boom, right in my head and I was like, “Maybe he doesn’t have to change.” I was so wrapped up and attached to him changing that I couldn’t see. I couldn’t see. I was wrapped up in my own perspective and I didn’t have a vision of what was possible.

Am I being clear about how this is really close?

When Sailing, the Gods Will Have Their Way with You

Now I’m going to move on to some pieces about sailing and the sea, and then we’ll move into Crowhurst’s journey. One of the reasons why I was asked to do this presentation was in 1991, I was part of a crew of four that sailed across the Atlantic Ocean in a sailboat. A 39-foot Camper & Nicholson that left Newport, Rhode Island. I forget the dates, but it was around June-ish and we arrived in the Azores nearly 20 days later. We spent about seven days in the Azores and then we went on to England, to Gosport, which is a coastal town in the Southern part of England. That took 12 days. I was at sea for 18 days and 12 days, so it was only 30 days at sea. There are a couple things I noticed about that, and about how it relates to Crowhurst.

The first is, when Crowhurst sets out and his boat starts to break down a certain way, that is just part of what happens when you’re at sea. When you’re in a boat in the middle of the ocean and being tossed around, things break. We had things break: at one point, our boom broke in a storm, and at another point, we thought we didn’t have oil pressure so we couldn’t run the engine. All this stuff happens at sea because you’re in a little teacup bouncing around on the ocean. When you talk about hubris, it’s like, “I’m gonna make it across the ocean.” Right? It’s like, “Really? You really think you’re gonna make it?” Cause you really don’t know. But when we set out, I was like, “I’m gonna make it.”

The first is, when Crowhurst sets out and his boat starts to break down a certain way, that is just part of what happens when you’re at sea. When you’re in a boat in the middle of the ocean and being tossed around, things break. We had things break: at one point, our boom broke in a storm, and at another point, we thought we didn’t have oil pressure so we couldn’t run the engine. All this stuff happens at sea because you’re in a little teacup bouncing around on the ocean. When you talk about hubris, it’s like, “I’m gonna make it across the ocean.” Right? It’s like, “Really? You really think you’re gonna make it?” Cause you really don’t know. But when we set out, I was like, “I’m gonna make it.”

There were a couple ways I got schooled related to this. One was when we were sailing, about the fifth or sixth day out, the weather report came in and there was a large tropical depression coming. It was pretty significant and I started to get a little scared, because when you’re in the middle of the ocean, you can’t throw out an anchor and say, “Well, I want to take a break.” You’re there. So we got hit by this storm and when you’re in the middle of the Atlantic and you’re on a sailboat and the waves are 25 to 30 feet high and you’re on a 39-foot sailboat, you have to just pull the sails in and surf down the waves as they come up underneath you. You can only run with the storm.

We were doing that and we got knocked down two times. “Knocked down” means the mast was about horizontal, and I was holding on with my elbow around the winch with my legs dangling, and then it righted itself. That happened twice. It was a sublime experience. It’s one thing to say, “Oh, the gods really had their way with us.” Right? But this is what people experienced like 2,000 years ago when the gods were really having their way with them, from their mindset.

It’s really humbling and I remember the moment when we were surfing down these waves when I said to myself, “Today’s the day. Today’s the day I’m gonna die. There’s nothing I can do about it.” There was nothing I could do, there was nothing I could say, there was no line I could pull, there was no trick out of my hat that would change that. And when I admitted that, my fear went from an 80, 90, or 100, down to about 20 or 30. I was like, “Well, I’m not dead in this moment, so I can do this, this, and this.” It really is a relationship with the present moment in relation to what the gods are doing. I was intimately linked with what was happening right there and not knowing what was going to be next, because you just don’t know.

Sailing Requires Some Skill and a Lot of Luck

The other part of the story, which kind of made me understand some things in terms of my ego was after I sailed across to England, I took some really nice trips and I did a bunch of sailboat racing in Rhode Island for some time, for a couple of summers. One time I was in a race off the coast of Long Island, and we pulled in and I was looking at the boats and wanting a boat. There was this beautiful boat and I encountered this captain of the boat who was a Jamaican guy and I was like, “Oh, yeah, I’ve done this and I’ve done that” because the sailing community is all about ego and about boasting. It’s intense. Anyway, I was doing that, right? I was like, “Oh yeah, I sailed across the Atlantic,” and this guy said, “Ah, you’re lucky. If you did that, you’re lucky.” There was some kind of truth being spoken to that. I didn’t quite understand at the time but what I’ve come to understand is I was lucky. You get out of these situations with some skill, and a lot of luck. That’s just the way it works.

Crowhurst’s Race

Crowhurst’s race was about the same. The sea will have its due and you can’t control for that. So you take a guy like Crowhurst, who believes, “I’m brave. I got the world in the palm of my hand. I’m doing it, right?” He had the real makings of the psychotic predicament. His history and the world are going to have “a collision of currents.” Crowhurst tended to get very wrapped up in trying to fix things, and really not understanding what was going on outside of him. When you’re in a situation like that, it’s really important to have a horizon point that you’re going toward. If you don’t have that, then you have really lost your way. Crowhurst’s horizon point became his mind and all of the things on his boat. It was an internal reference, and not an external, “I’m going there.”

There is a little jiu-jitsu trick of the mind when you are in the ocean and all you see is water. When all you see is horizon and everything that you see is the same in every direction, it’s very disorienting. You don’t know where you are, so in your mind, you have to have some fixed point somewhere that you can visualize. While we were traveling, it was the Azores. We focused on how “we’re gonna get to the Azores.” And it was really fabulous when there was finally land and we’re like, “Oh my God, there’s land. Thank God there’s land.” Then you gain perspective, thinking, “Oh yeah, that was a bad storm.” For Crowhurst, he lost that trajectory and became really involved in his image and all these details related to his boat and the race.

Group Discussion

Gary: Any questions about sailing, sailboats, things of that nature?

Audience member: How much harder is it to do it by yourself?

Gary: Oh my God. You have to deal with sleep. You’ve gotta sleep and when you sleep, what do you do? Well, there’s all sorts of alarms that they have to wake you up if you go off course. Again, when you are alone, the journey becomes much more difficult. One of the things that Podvoll alludes to when he talks about recovery is that what we need is connection with other people.

If you don’t have connection with other people and you’re projecting onto the sublime nature of the ocean and everything that that entails, you can lose your mind. You can really lose your mind because there’s nothing to grab onto. One time, I was sailing across, and to take a shower, we would jump off when it was warm, come out, soap up, jump in. So I was swimming in the Atlantic and I look down and open my eyes and every part of my vision was aqua, and you know it’s two miles down. That’s really humbling. It’s two miles down. All I see is aqua. You really get it that you are very small, very small. There’s all sorts of ways that the ocean can really play on your mind. It can really evoke senses of smallness and just . . . I love when Jacques Cousteau says that when people enter the ocean, they enter the food chain, and not necessarily on top. It’s a very big place and it is unforgiving.

And to be out there on your own is even more of a challenge.

So when I set out, I was prepared to take the world on. Obviously, life has its way of correcting us and luckily, I listened. Crowhurst didn’t quite listen. He had very small islands of clarity in his doubt, but that quickly got covered over. He didn’t live in relation to what was happening around him in terms of the environment and himself. He quickly retreated into his fast mind to make himself larger and larger. I imagine he tried to make himself larger than the circumstances.

Audience member: Crowhurst eventually stops relating to the sailboat and situation, and starts focusing entirely on the log books or what he’s generating in there. He’s absorbed in the fact that the two log books are different.

Gary: He’s trying to manufacture the experience as opposed to paying attention to the reality of what’s going on.

Audience member: And he uses the ability to manufacture the log books as a way of having some sense of control over something he’s creating, as opposed to a situation over which he has no control, essentially.

Audience member: Something that sticks out for me related to Crowhurst’s experience in this story, is the wall of external pressure: of both his own observation and that of the world’s eyes on him. Right off the bat, he pretty much decides that he needs to start creating this fraudulent record in an effort to save face.

The book also the mentions that part of Crowhurst’s reason for doing that is being with all these people that invested all this money in him and in his boat. There was this sense of “I’m gonna let them down if I don’t do well in this race.” And even his initial reason for doing this boat race was to draw publicity to a company of his. So much of his motivation related to other people’s perception of him.

Gary: What comes to mind related to that, in terms of a psychotic predicament, is our own personal experiences and the external circumstances colliding. For Crowhurst, the potential energy of that collision was huge, given his life. He was so invested in people seeing him doing good and being brave and all this stuff. The potential energy of that creates the pressure of “Oh my God, I’ve gotta make sure that all this holds together and. . .” And the more those internal and external experiences collide, the farther and farther apart the log books can get. And then the idea of how do you square these two can become what seems like an impossible design.

Audience member: I was just thinking about how so much of this relates to identity: where we see ourselves, our ego, and what happens when there is a mental health diagnosis. What it is like to identify with being a “sick person” or the complexity and the pressures of having multiple identities. Often people are taught to identify with themselves as being really special. And there can be an expectation from parents that their kids should be really brave, and be amazing. How there can be a disconnect from that expectation, and how there isn’t room for imperfection.

Gary: Right. The force of circumstance becomes the family, or another image, or even Windhorse, right? Then there’s the collision, again there’s potential energy in the collision.

Audience member: What I’m having the strongest reaction to in the chapter is the letter that he left to his wife before he set sail. She found the letter four months into his journey. I guess he had to deal with the fact that he may die on the voyage and he talks about how he’s not afraid, and never has been and never will be. Instead, he’s only deeply concerned about the consequences for his wife and the children that he loves only second to her. It blows me away that, with those relationships in his life, it’s hard for me to see how they didn’t sustain him, and help him to say nevermind the ego. I’m surprised that his attachment to his ego could supersede his attachment to these dependent beings.

Gary: That points to the seeds of self-destruction. That’s how powerful the ego is when it gets roaring.